Jake McLemore’s father was Charles Taylor “Charlie” McLemore.

Charlie grew up during the depression, traveling with his father, Lee Allen, on trains, with other hobos, with the putative goal of finding work. When the crash hit the oil industry, it took longer than for most other industries, but eventually the bottom fell out of the oil business in 1932. The wells were capped and the rigs hauled away, leaving the men who had depended upon the work stranded in small oil patch towns with no other opportunities for work. Many of them joined the large numbers of itinerant men riding the rails. Some looked for work but many had given up and made do as best they could.

But when we think of hobos riding in boxcars we don’t usually think of children doing the same thing. But when families had no money, little food and nothing on the horizon, they simply sent their children away to fend for themselves, as best they could.

“At the height of the Depression, as many as a million teenagers traveled the rails looking for work and community, moving in vagabond packs and living in hobo jungles, finding both charity and brutality in the broken-back cities of America. They crowded the cars and hid down in the tenders where the coal and water were stored; they squeezed between cars and clung atop their bucking roofs. In 1932, about 75 percent of the nearly six hundred thousand transients on the Southern Pacific line through Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona were under the age of twenty-five.”

“Fathers, and sometimes sons, stayed in the network of “jungles” along the route, tucked amid the timber and hidden from view. Each camp had its own division of labor—one person went into town to find a potato for soup while another brought salt or an extra spoon. Pots and pans hung from tree branches; crude shelters were made from cardboard or tin scrap and sometimes built up in the trees. Pocketknives were like gold in the jungles. Blades were “hired out” in exchange for soap or a bowl of stew. In a pinch, a knife could be traded for a pair of shoes or sold for cash. Men cooked possums and jackrabbits caught in snares along the brush lines and traded their hides for food.” (Mealer, Bryan. The Kings of Big Spring: God, Oil, and One Family’s Search for the American Dream. 2018.)

This was the kind of life Charlie McLemore lived during his childhood.

Charlie and his father worked picking cotton in California for a few weeks and also fruit when they could. They managed to work just enough to feed themselves, as well as, put a little aside. Eventually they got back to Oil City just as things were starting to come back.

By the time World War II started, and a need for oil exploded, Charlie was in his late teens. His father got work immediately at a refinery and from then on, the Lee McLemore family did okay.

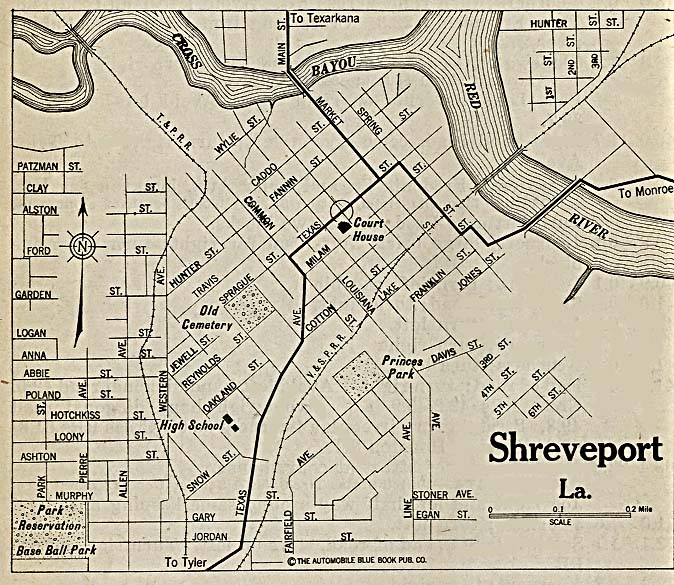

Charlie went into the oil business as well, but oil was not the only resource product that supported the Oil City economy. Natural gas was even more abundant and Charlie got a job at United Gas Corporation, headquartered in Shreveport, Louisiana, and moved his family there in 1960 a year after Jake was born.

Charlie worked at United Gas and survived the hostile takeover by Pennzoil in 1968, and became part of the management of Pennzoil United, Inc. He did pretty well, well enough to send his son Jake to Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Retiring at the age of 70 in 1991, Charlie lived long enough to see Jake get married and have children. Charles Taylor McLemore died in 2001 at the age of 80 from a heart attack a few months before 9/11, and several years before his grandson Lee’s death in 2004 in Iraq.

Despite surviving the Great Depression by riding the rails with his father, he was among the generation that experienced the economic boom after WWII. Charlie McLemore saw nothing in his lifetime that undermined his faith in the American Dream. A dream he lived out to the fullest.